After decades of European construction where Member States became increasingly connected and interdependent, the current rise of populism in Europe is concerning. Recently, the Constitutional Tribunal of Poland, close to the national-conservative government, ruled that some European laws were incompatible with its constitution. Through this example, we can observe one main populist argument : the threat that the European Union represents to the national sovereignty.

However, before starting to give a thought to this phenomenon, it’s important to know what it stands for. Indeed, the notion of populism comprises various forms and is not only linked to far-right politics. In his book Popolocrazia: La metamorfosi delle nostre democrazie published in 2018, Marc Lazar insisted on the fact that left-wing and right-wing populism can’t be assimilated but have although similar characteristics such as the rejection of elites and the ruling class, the rejection of globalization and the contest of some aspects of liberal-democracy. In general terms, we understand by populism, referring to the Oxford English Dictionary, a « political approach that strives to appeal to ordinary people who feel that their concerns are disregarded by established elite groups »

Then, how can we explain the construction of the populist thought in the European Union ? To what extent is it an indicator of a lack of confidence and knowledge about the European institutions and their operation ?

I will first do a brief analysis of the populist speech, which consists in saying that elites govern Europe. Then, through an historical approach of the European institutionalism, I will demonstrate that this speech is pronounced by leaders that play with the people’s fear and lack of confidence and knowledge about the European institutions and their prerogatives.

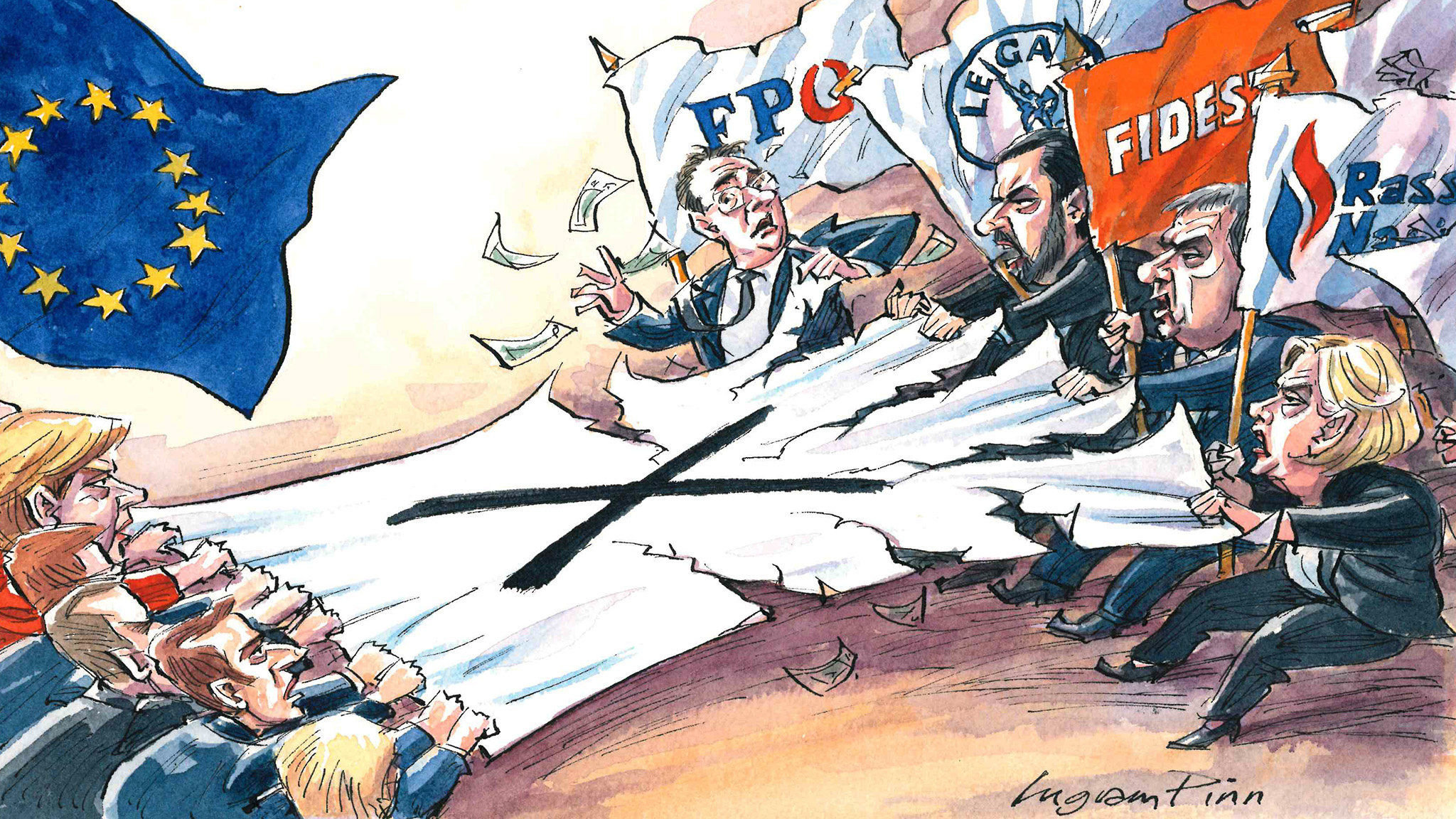

One way to understand the construction of the populist thought is to observe the link it has with elites. If the programs can vary between countries and political positions, there are certain constants in the populist ideology. The denunciation of elite and supranational institutions are two of them. It seems that populists develop a Manichaean rhetoric based on a simplification of the reality. Indeed, their speeches are full of divisions : the « big » against the « small », the « elite » against the « people »… This is something that we can perceive in France with political parties such as France Insoumise or Rassemblement National where Germany is denounced because, for them, it governs Europe and only seeks its own interests. This idea can also be found in Central Europe where some countries feel abandoned by the European Union and feel like rich countries are the real decision-makers. This Manichaean rhetoric creates a fear for the national sovereignty and leads finally to radical politics and decisions. Brexit or the recent affair in Poland are two pertinent examples. David Miliband illustrates it in an article published in Horizons[1]Miliband, David. “Brexit, Populism, and the Future of British Democracy.” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, no. 15, Center for International Relations and … Continue reading about Brexit and populism. Also, populism is at the origin of a second rhetoric of division which consists in opposing a « them » to a « us ». This particular point is one of the major differences between left-wing and right-wing populism. Usually in this division there is the claim of preserving the national identity which is undermined by the European Union threw migration policies or border controls and taxes for example. There is also the idea that multiculturalism and globalization are weakening the nation. When populist parties call on the weakening of the Nation, it can stand of course for the State itself (like the Rassemblement National) but also for regions (like Lega Nord in Italy or Vlaams Belang in Belgium). This conception is specific to right-wing populism as the left-wing shares a different thought on these questions. Furthermore, the populist reflexion, threw its simplification of reality, leads to the creation of a common enemy : ‘Brussels’. In their imaginary, Brussels is the place of the elites, of the abandonment of their national sovereignty in aid of Germany or the rich countries. It represents the ideal of what they want to fight. It seems that there is a deep correlation between populism and euroscepticism. We understand that this phenomenon comes from a lack a confidence in the institutions due to a lack of understanding of its prerogatives.

Indeed, the populist political parties are playing with the people’s fears and lack of knowledge to put EU in the position of scapegoat. In this part, we’ll try to develop through the history of the European institutionalism that the idea that an elite or a country is running the EU is false. Admittedly, countries agreed when they joined the European Union to put in common some of their decisional powers in some domains. However, they did it legally, with sovereign rights and decided to respect the European treaties. Also, it’s important to understand that to the idea that 80% of law adopted in the Member States originate in Brussels, like the leading candidate of the Rassemblement National in the European elections of 2019 said it, is erroneous. A survey realized by the French progressive think tank Terra Nova shows that in fact that this number is only between 10% and 30%[2]Matthias Fekl, Thomas Platt, « Normes européennes, loi française : le mythe des 80 % », Rapport Terra Nova, 2010. URL : … Continue reading. Therefore, most of the measures adopted by the Member States don’t come from the European Union but from the legislative and executive powers of their country. They legislate by themselves. For example, when a Member State decides to reduce the speed limit or to prohibit religious signs at school. With those elements, we understand that being a member of the European Union is definitely not the sign of a weakening of the national sovereignty. Nevertheless, it is true that European laws take priority over national laws when they exist. It’s the case, for example, for the limit of polluting emissions for car manufacturers. In addition, when the European Union legiferates, it doesn’t mean Member States don’t have a word to say. The EU can’t be reduced to the single European Parliament : Member States have a role to play in institutions like the Council of ministers or the European Council. Also, the European Union competences are not the same and depend on the different domains. In some cases (monetary policy, foreign trade, concurrency…) EU has exclusives competences. But in most cases (13 domains), the competences are shared between the EU and the Member States.

To conclude, the populist thought in Europe seems to emanate from political leaders who rely on the lack of knowledge of the population regarding the European Institutions. In a context of social, sanitary and migration crisis, this is why the designation of a common enemy (the elite, Brussels…) seduce more and more people. This reveals that there is a big work of vulgarization to do with the European citizens so that they can discern the political speeches and take a critical look at them. Being in disagreement with the actual European system is lawful and good for our democracy and the guarantee of the plurality of opinions. However, it’s important that those who are against the actual system are against it for the good reasons and have a strong and deep understanding of its operation and that they don’t contribute to an erroneous and secessionist speech.

Bibliography

- Coutrot, Thomas (2018), “Existe-t-il une politique économique populiste ?” in Badie, Bertrand and Dominique Vidal (2018), Le retour des populismes, L’Etat du monde 2019, La Découverte, Paris, pp. 110-117.

- Lazar, Marc (2018), “Populismes de droite, populismes de gauche en Europe”, in Badie, Bertrand and Dominique Vidal (2018), Le retour des populismes, L’Etat du monde 2019, La Découverte, Paris, pp. 118-125.

- Eric Sylver (2018), “Europe’s Populist Left and Right Share a Common Call: State intervention”, The Wall Street Journal, 12-14-2018.

- David Miliband, “Brexit, Populism, and the Future of British Democracy.” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, no. 15, Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development, 2020, pp. 150–65.

- Matthias Fekl, Thomas Platt, « Normes européennes, loi française : le mythe des 80 % », Rapport Terra Nova, 2010.

- Pauline Moullot, « 80% des lois votées à l’Assemblée viennent-elles de l’UE, comme le dit Bardella ? », Libération [en ligne], 12 avril 2019. URL : https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/2019/04/12/80-des-lois-votees-a-l-assemblee-viennent-elles-de-l-ue-comme-le-dit-bardella_1720715/

- Pierre-André TAGUIEFF, « POPULISME », Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne]. URL : https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/populisme/

Notes

| ↑1 | Miliband, David. “Brexit, Populism, and the Future of British Democracy.” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, no. 15, Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development, 2020, pp. 150–65 |

| ↑2 | Matthias Fekl, Thomas Platt, « Normes européennes, loi française : le mythe des 80 % », Rapport Terra Nova, 2010. URL : https://tnova.fr/democratie/politique-institutions/normes-europeennes-loi-francaise-le-mythe-des-80/ |

In english or not….. FREXIT!!!!

Et maintenant des articles en anglais, on ne t’arrête plus ! Je t’avoue que je suis légèrement largué en terme de langue… si tu peux me résumer les grandes lignes en français ce serait avec plaisir.

Ne partageant pas les mêmes idées que toi je ne peux pas dire que tes articles politiques m’avait manqué… Toutefois tu reconnaiss toi même que l’Europe outrepasse certains droits avec la primauté de son droit existant sur le droit national souverian hérité du peuple… à méditer donc

Son article, très nuancé et n’évoquant absolument pas un quelconque « outrepassement », mériterait une relecture de ta part ? 😉